Drowning Prevention for Everyone

Understanding Dangerous Currents

Dangerous currents and breaking waves are common in the Great Lakes region. Rip currents and other currents found near piers are extremely dangerous for swimmers and can lead to drownings. These illustrations from Michigan Sea Grant depict various dangerous currents, to help you spot them and know how to escape them.

Rip Currents

You may have heard of rip tides or undertows. However, since there are no tides in the Great Lakes and currents don’t pull a person down under the water, they are inaccurate terms.

Rip currents form when waves break over a sandbar near the shoreline and the water and its momentum get trapped between sandbar and shore. When the water and the momentum build up, the water has to go somewhere. One of the ways the pressure is relieved is when water returns to the lake in the form of a rip current, a narrow but powerful stream of water and sand moving (ripping) swiftly away from shore.

Rip currents will not pull a swimmer under the water. Instead, it will carry them out to the open water, away from shore.

To escape the grip of a rip, do not fight the current – even an Olympic swimmer cannot – swim to the side; Flip, Float & Follow the safest path back to shore.

Read compelling stories from rip current survivors, victims’ family and friends, first responders, and others who want to help prevent drownings here.

Structural Currents

While it can be difficult to predict when and where most currents will occur, the opposite is true for structural currents. The currents found alongside or as a result of structures like piers and breakwalls — called structural currents — are usually always present.

Structural currents are dangerous on their own, but when paired with others like longshore or rip currents, and when colliding with incoming waves, the combination can create a washing machine effect, moving the swimmer from one dangerous current area to another with no clear path to safety.

Steer Clear of the Pier – Avoid jumping off or swimming near piers. The currents found along these structures are often dangerously strong.

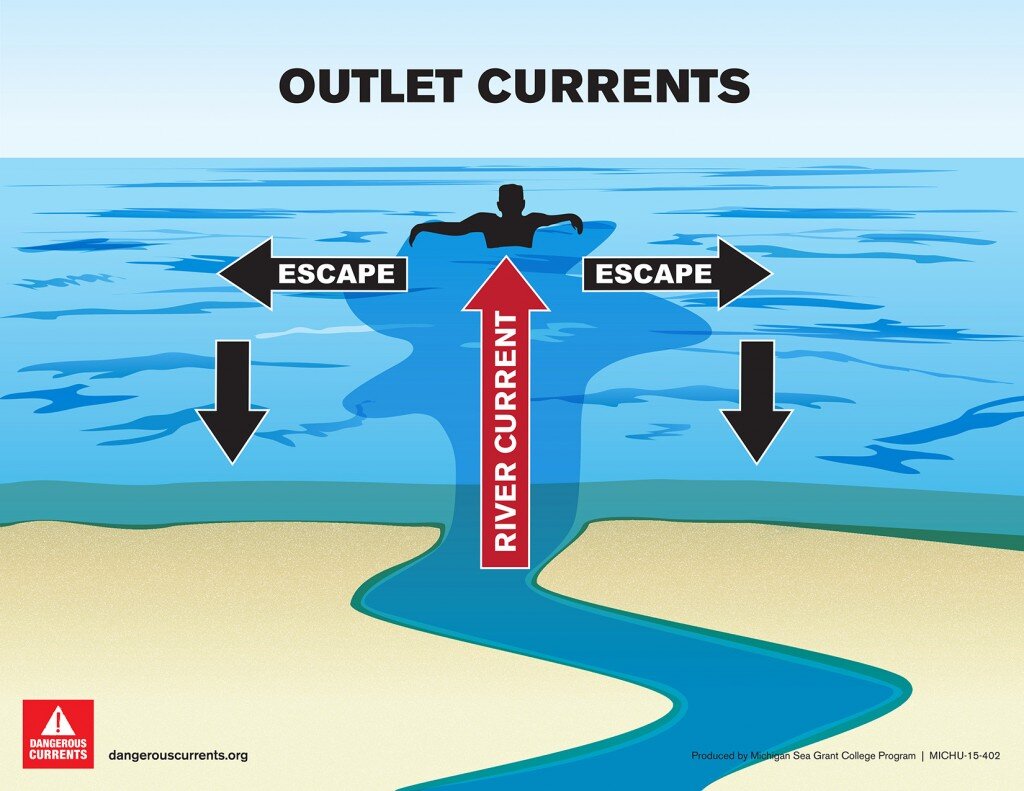

Outlet Currents

Outlet currents can be found where rivers and streams empty into the Great Lakes. The flow of water from the river or stream can move quickly. As it enters the open water of a lake, it may take awhile for that current to dissipate. Pair that with currents that are present in the lake and the situation can become dangerous.

Note that in some channels and river outlets the current can change direction, making them even more dangerous.

While they are tempting to swim in because they are often warmer than the lake water, avoid swimming in or near outlets.

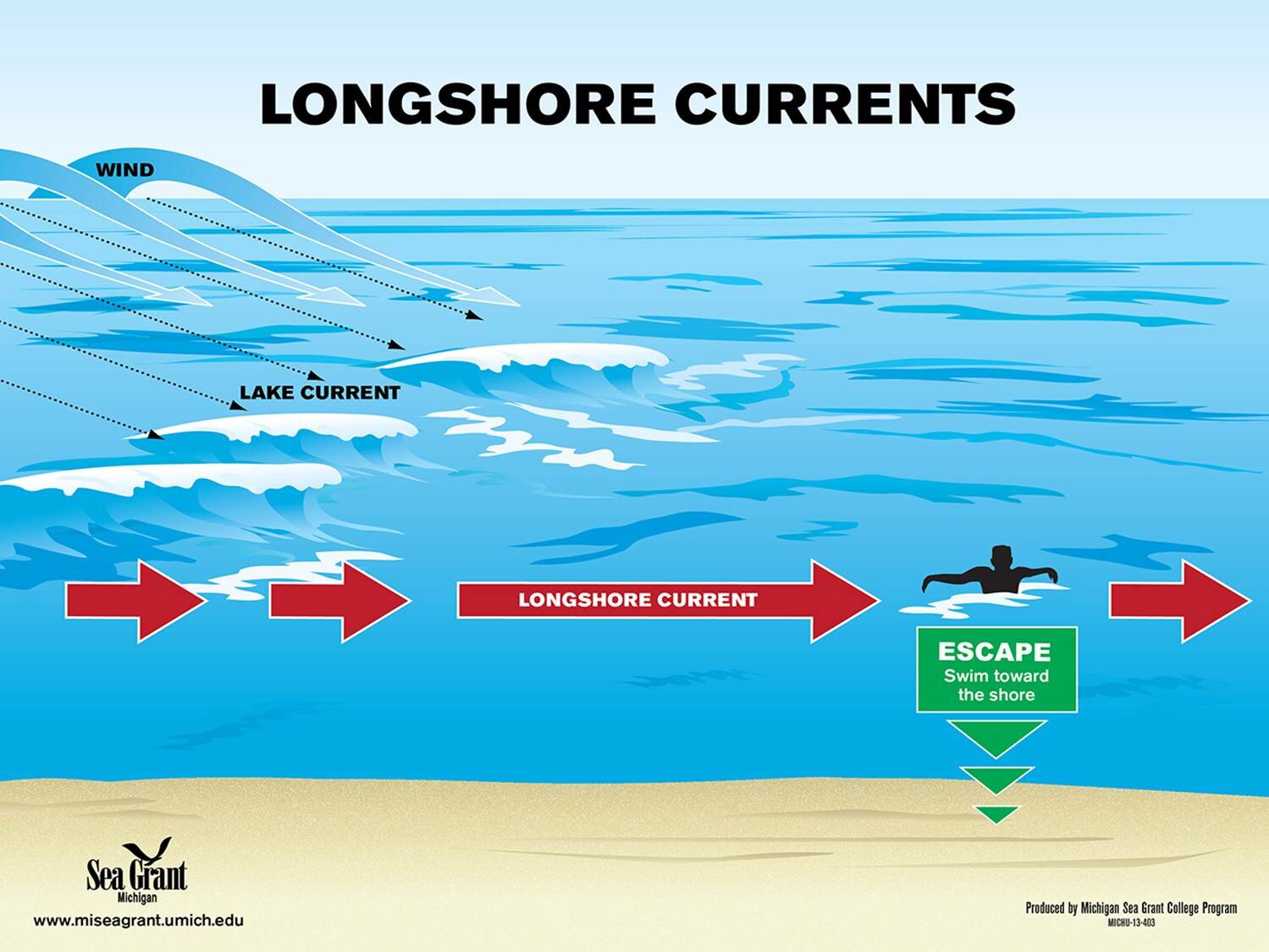

Longshore Currents

As the name suggestions, longshore currents move parallel to or the “long” way along the shoreline.

These currents will exert a force to move along shore, making it difficult to remain in front of a spot on the beach. They often happen between the first and second sandbars near the shore.

Longshore currents become more dangerous when they combine with rip currents or structural currents since they can move a swimmer swiftly down a beach and into the path of another current or into a structure (pier or breakwall), making it more difficult to swim to shore.

Be aware of longshore currents that may carry you toward structures. Stay at least 100 feet away from any structure.

Channel Currents

A channel current is like a river running parallel to shore. With a channel current, typically there is an island or structure such as a large group of rocks not far from shore. A channel current forms when the flow of water speeds up as it goes between the island and shore, like a bottleneck.

This is made worse by the presence of a submerged or partially submerged sandbar connecting the beach to the island, which allows pressure to build behind the water and waves until it breaks through. When the wind speed increases, the waves also increase in intensity, and this causes the current to become stronger and faster.

The best escape route is to swim to the shore, not the sandbar.

Three Ways You Can Make A Difference

Advocate for Lifeguards

Lifeguards are the superheroes of the Great Lakes. Unfortunately, even though the Great Lakes can be more dangerous, you see more lifeguards at the oceans than here.

Tell your community and park leaders that you want your beach to be the safest, and that means investing in lifeguards – no excuses.

Advocate for Warning Signs & Systems

Where there are no warnings, people assume there are no dangers.

If you don’t see beach warning signs or flag/LED warnings systems at your favorite beach, let workers know you expect them, because not everyone knows what you know about staying safe in different conditions.

Advocate for Rescue Equipment

If there are no lifeguards and someone is in distress, untrained beachgoers may choose to try and save them, and often become victims themselves.

Liferings or other flotation devices are key to safely saving someone. If you don’t see any at your beach, let community/park leaders know you want to see safety improvements every year.

Haven’t been able to join us at a conference? Watch our Virtual Water Safety Jam Sessions instead.

We were holding one or two Great Lakes Water Safety Conferences in various states over the past several years, and had our biggest ever planned for Traverse City in 2020, when the pandemic hit.

We quickly pivoted to a series of Virtual Water Safety “Jam Sessions” with a variety of experts on a variety of drowning prevention topics, and they were a big hit.

Watch them on our YouTube Channel here:

Jam 1: Opening Great Lakes Beaches in the Wake of COVID-19 – Laura Rowen, Adam Bueling, Mark Breederland, Dan Metcalfe

Jam 2: Nudging People Toward Being Safer Around Water – Susan Och, Jamie Racklyeft

Jam 3: The Impact of High Water Levels & Beach Erosion on Public Safety – Matt Warner, Mark Breederland, Jason Wintermute, Dan Metcalfe

Jam 4: Translating Wave & Current Science Into Better Forecasts & Warnings – Dr. Guy Meadows, Bob Dukesherer

Jam 5: Lessons Learned From Consecutive Drownings & Great Lakes Hotspots – Liz Reimink, Halle Quezada

Jam 6: What Every Kid (and Their Parents) Should Know About Water Safety – Harve Norris, Becky Epstein, Captain Drew Ferguson

Bonus Jam 1: Justifying and Starting Up a Lifeguard Program in Your Community – Scott Ruddle, Cheryl Podtburg, Tim Jaskiewicz

Bonus Jam 2: Boating & Watercraft Safety – Commander Matthew Walter & First Class Cadet Grace Tarbrake (USCG), Captain Drew Ferguson, Dan Metcalfe

Learn more from TED

Hear our founder’s moving rip current survival story and how he describes our Top 10 Lifesaving Tips in the first-ever TED Talk on water safety.

Interested in more rip current stories or in sharing your own? Click here.